301 Moved Permanently

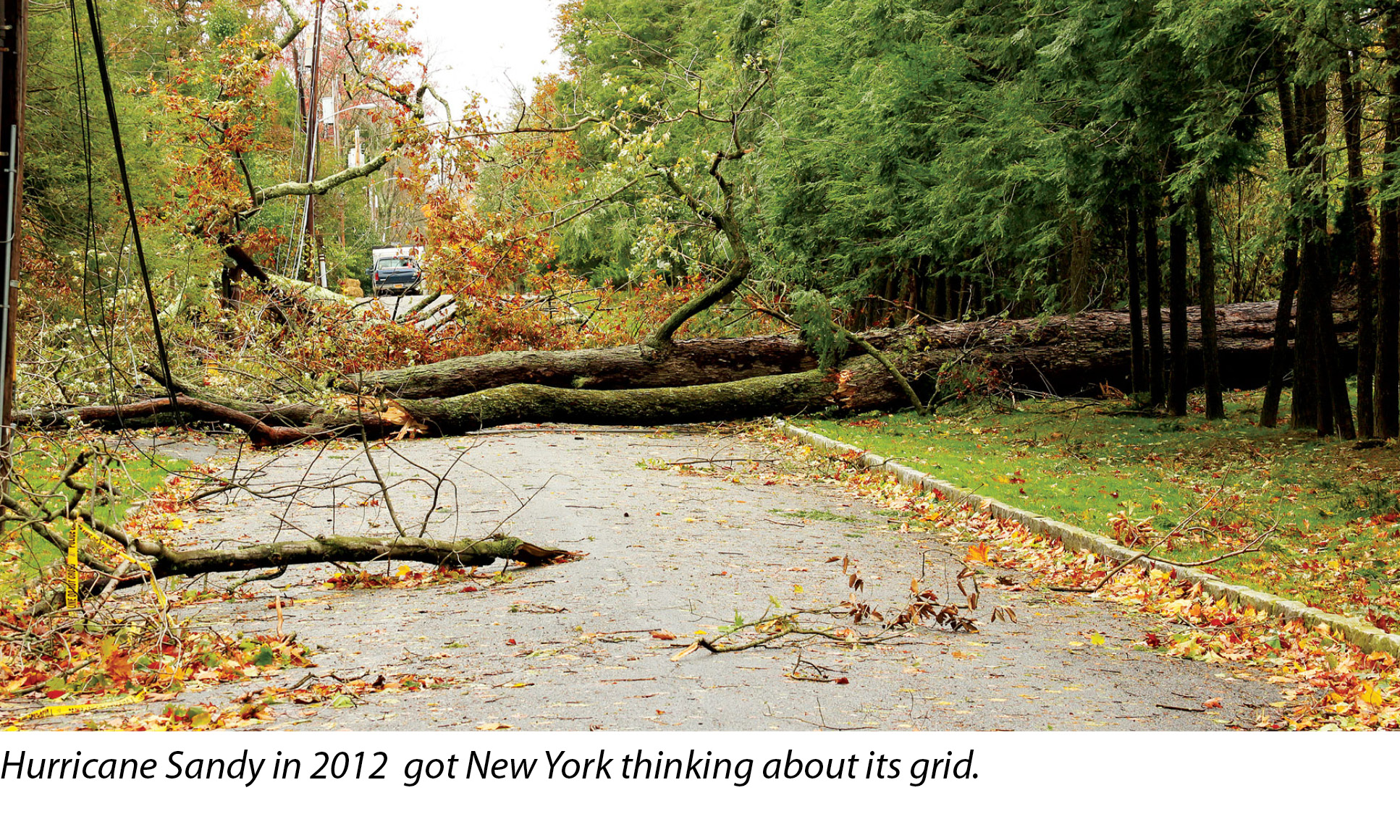

Hurricane Sandy is proving to have a durable impact on the minds of many energy planners. Not only is it referenced in the desirability for residential and commercial storage systems for providing emergency backup power - ideally in connection with solar generation - it now features in an ambitious plan to remake the grid.

The New York Public Service Commission (PSC) has embarked on its Reforming the Energy Vision (REV) program that seeks to reorganize the state’s energy industry and regulatory policies to produce a more resilient grid. Essentially, the culmination of the effort is creating a network of microgrids that would have the effect of putting distributed generation (DG) solar power on an equal competitive footing with centralized power plants.

Under the REV plan as it currently stands, utilities are the go-to actors for making this transformation happen. As part of this initiative, Gov. Andrew Cuomo has approved an energy management program for Con Edison intended to encourage the deployment of local energy resources in areas that provide value to the larger electric grid, offer renewable energy generation and encourage competition.

The so-called Brooklyn Queens Demand Management (BQDM) program is expected to lower overall costs for customers while offsetting the need to build a $1 billion substation. Cuomo is encouraging utilities and other potential parties to propose additional demonstration projects along the lines of the BQDM. The PSC says these demonstration projects should showcase new business models that improve the resilience of the electric distribution system and add local energy resources and technologies to the grid.

James Tong, vice president of strategy and government affairs at Clean Power Finance in San Francisco, says that although he appreciates the expediency of employing utilities in this role, he nevertheless has some issues with REV from a public policy perspective.

“Not only would the utilities favor their monopoly assets, but New York is also thinking of allowing the utilities to rate base distributed resources, including rooftop solar,” Tong says. “And now you can see a huge conflict of interest in that.”

From conflict to marketplace

Necessity and hurricanes may be mothers of invention in this regard, which is why New York is out in front nationally on this concept. A network of microgrids would function like the Internet in that the whole system would be more survivable. The idea is not to have a bunch of stand-alone islands, but to integrate them into the larger grid, as well. While some systems may go down in an emergency, other systems would continue to function, enabling power to be rerouted around trouble spots in a dynamic way.

“What you are going to need is coordination within the microgrid itself and then coordination across the microgrids,” Tong says. “In the context of what is happening in New York, there is recognition that we want to use these distributed energy resources - whether it’s rooftop solar, battery, electric vehicles - and be able to coordinate them in a way that maximizes the benefits to the grid.”

However, opportunities for creating energy markets at the distribution level extend far beyond disaster recovery and grid resiliency. As Tong sees it, the challenge is in trying to coordinate all of these technologies. As he told a panel audience at the recent Solar Power International (SPI) conference, without coordination, many of the new DG and energy-efficiency technologies will produce chaos on the grid. The idea there is to create a new role in which somebody coordinates the planning, deployment and real-time dispatching of the different resources. But, who gets to fill that role?

In a paper he co-wrote with Jon Wellinghoff, former chair of the U.S. Federal Energy Regulatory Commission and now a partner at Stoel Rives LLP, Tong proposes that the model used at the transmission level, in the form of regional transmission operators and the independent system operators working under the supervision of the federal regulators, be replicated at the distribution level with state regulators in the overwatch position.

Under this concept, a distribution system provider (DSP) - also called a distribution system platform provider - would be the independent entity that would fill the role of microgrid network coordinator. Looking around the industry, however, the utilities again seem to be the only parties placed to assume the DSP mantle. The key to making this work would be to disconnect the utility’s power generation function from its transmission and distribution (T&D) infrastructure planning, maintenance and operations functions.

The fact that utilities operate as a natural monopoly in the public interest is what makes them useful potential candidates as DSPs. As T&D forms a significant portion of a utility’s existing expertise and responsibilities, it is well equipped to handle the physical requirements of the DSP. Also, public utilities are already subject to state regulation and, thus, are structured to have their earnings subjected to regulatory discipline in lieu of market discipline.

“In the current system, the only way the utilities recover costs is through selling kilowatt-hours,” Tong says. “This is, essentially, a taxing mechanism. What we’re saying is, ‘Don’t worry about how you recover the costs. Worry about how you make investments, because the regulatory body will ensure that you are able to recover the costs.’”

Tong says the goal is not necessarily to get utilities to divest from power generation assets - though this could be helpful. The goal is to make sure the grid operator is a neutral party that truly serves the public and not just the incumbent utility. The issue, as Tong sees it, is whether the owner of the T&D infrastructure - really, in this case, the distribution infrastructure - can use its monopoly power to favor its assets over those of third parties.

One argument says the removal of generating assets from a utility’s portfolio could be a blessing in disguise. While T&D assets remain functionally the same, except where they may be modernized by improved technology and intelligence, Tong points out that the power generation fleet is apt to be “ravaged” by new DG technology coming online, with more to come as national priorities change.

But the blessings are not all due to avoidance of bad outcomes. Tong says that in their new incarnation as DSPs, utilities will be able to reinvent their business models along the lines of Apple Computer and its App Store for portable devices, such as iPhones and iPads.

Under this model, there is a network of providers marketing different services. It is doubtful that the utilities would be in a position to provide all of these services to their different customers. There would have to be different specialists - DG energy providers, financing companies, smart appliance companies, software companies - with the utilities hosting all of these capabilities.

Rob Caldwell, senior vice president for distributed energy resources at Duke Energy, told the SPI panel that his utility was pursuing a number of demand response (DR) programs across all of its jurisdictions.

“I think you can take advantages of smart technologies in the home and tie those with smart technologies in the distribution center,” Caldwell said. “I think we can take advantage of the technology in the DR space and then marry that with technology in the DG space to manage both more cost-effectively.”

The problem is that there is not just one distribution system, even within the service area of a single utility. Each one of Duke Energy’s distribution systems is designed and set up differently. Therefore, Caldwell said, each has to be managed differently. Differently means more money.

This is less of a problem than it first appears, Tong replies, because the utility, as the T&D infrastructure provider, would be in a position to both coordinate how it is used and receive compensation for its trouble.

“If you use the iPhone analogy, what I’m saying is that at the end of the day, the T&D infrastructure is a piece of hardware,” Tong says. “It’s a big piece of hardware, but it is hardware. That hardware can host a marketplace of different providers.”

The utilities would enable a marketplace of energy providers - central and DG - and energy-efficiency technologies that all make use of the hardware platform. The utility would have the ability to vet the generators and technologies using the T&D infrastructure while receiving revenue through transaction and access fees.

The whole point is that by trading in this marketplace, it actually makes it more valuable to the third-party providers on it.

“Right now, third-party providers feel that the utility is in direct competition with them,” Tong says. “But when utilities host a marketplace, third parties will see it as complementary and, in fact, facilitating their business. There would be more willingness to accept the fees.”

As for the utilities, there would be more of an opportunity - and incentive - to invest in, upgrade and maintain the hardware that the third-party providers are developing products and services for, all the while paying for the privilege of using the hardware.

“The challenge here is that the hardware infrastructure is a natural monopoly, whereas Apple has to deal with competitive hardware,” Tong says. “So, you have to be able to curb - or at least put some controls on - how that monopoly can distort the marketplace. At the same time, we are reaffirming that there is a public interest in having the utilities maintain this monopoly, even in a distributed world.” R

Industry At Large: Transmission And Distribution Operators

Energy Planners Edge Toward A New Model Distribution Service Layer For DG Solar

By Michael Puttré

In their role as distributed resource operators, utilities would maintain the infrastructure for a marketplace of services.

si body si body i si body bi si body b

si depbio

- si bullets

si sh

si subhead

pullquote

si first graph

si sh no rule

si last graph