301 Moved Permanently

Distributed generation (DG) is increasingly seen as an attractive model for deploying renewable energy - especially photovoltaic solar power.

Part of the appeal of DG is that it locates generation sources closer to the loads. Most of the burden is on the local distribution system. The transmission grid, then, has that much less to carry. Solid-state PV projects can be placed in a wide variety of sites in midsize allotments so as to balance the distribution system and reduce the need for expensive transmission infrastructure.

Forward-thinking states, such as New York, California and Hawaii, are examining how to incorporate DG into their energy plans to achieve better grid resilience, renewables penetration and even wider access to green power. State legislatures and public service commission (PUC) regulators respond with rules, incentives and policies, such as virtual net metering, community solar and regional carve-outs, to promote the development and distribution of solar projects to meet these goals.

Though DG development programs and policies have widespread support across the solar sector, some independent energy companies that specialize in renewables regard them as a mixed bag. Rather than tinkering with rules and incentives, the argument goes, it is better to deregulate electricity markets.

Don’t legislate - deregulate

“The velocity of the technology change is much, much faster than the bureaucrats and the regulators can keep up with,” says Phil Van Horne, CEO of Blue Rock Energy Inc., an energy provider based in Syracuse, N.Y. “Energy technology is moving so quickly that we are going to end up with rules and regulations in place that don’t apply.”

Van Horne says New York is a good case study for how solar policies designed to enable DG can have unintended consequences. Although most of the state has deregulated energy markets for electricity and natural gas, the former is restricted on Long Island, where Public Service Enterprise Group (PSEG) Long Island is the sole electricity provider. Thus, Blue Rock is able to serve as an electricity provider throughout New York State, except Long Island.

“We can’t sell you electricity, but we can sell you a solar panel,” Van Horne says. “We can sell you demand-response technology. We can even sell you natural gas generation. All of that electricity comes off of PSEG Long Island’s bottom line. They end up with a shrinking-base phenomenon, where they just can’t keep up.”

As a utility’s customer base shrinks, it is forced to go back to the PUC and ask for higher rates, which it generally gets. After all, the utility is required to maintain the transmission and distribution infrastructure. Higher retail prices for electricity make the economic case for solar and other alternative generation sources even more attractive. And so the death spiral begins.

In some circles, this is called a feature, not a bug.

Nevertheless, Van Horne says, the phenomenon will eventually lead to a situation wherein only those customers able to afford some form of alternative generation, such as PV, will have a choice. The fewer choices there are, he argues, the higher electricity bills will be for those least able to afford them.

Russ Wright, vice president of sales and development for OneEnergy Renewables, a Seattle-based project developer, says electricity deregulation enables flexible approaches to provider and off-taker relationships that transcend local regulatory structure. The company’s so-called “Purpose-Built Solar” plans connect customers with providers within the same energy market, such as PJM and the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), that don’t require any mechanism other than deregulation.

“The idea is to take advantage of the deregulated structure to take a wholesale-to-retail approach to energy generation,” Wright says. “In New York, for example, the virtual net-metering programs are dependent on the Megawatt Block program and the regulatory structure. To a certain extent, the same is true with the community solar programs.”

OneEnergy works to identify a prospective customer and then works up a customized electricity off-take plan. Then, it matches the customer up with a project of a suitable scale and production profile that meets the plan’s requirements. Deregulation enables OneEnergy to build the generating project anywhere in the same market - PJM or ERCOT - even out of state.

“We have two basic assets that we’re pursuing: the project and the customer off-take,” Wright says. “Part of our job is finding the best way to pair those up.”

The ability to meet a customer’s demand with off-site generation gives OneEnergy a lot of latitude with regard to where the solar site is placed. One of the advantages is that sites can be placed in locations that help a utility balance its grid - fulfilling a DG role. At the same time, the project can be of a scale that is economical for the developer.

Wright says that OneEnergy’s approach is able to make use of state incentives and programs to make projects more attractive economically. For example, Maryland’s solar renewable energy credit (SREC) program provides the extra “kicker” needed for projects to pencil out. In Texas, however, where there is no SREC market, Wright says the production a project can achieve with trackers makes it competitive with local wholesale electricity costs.

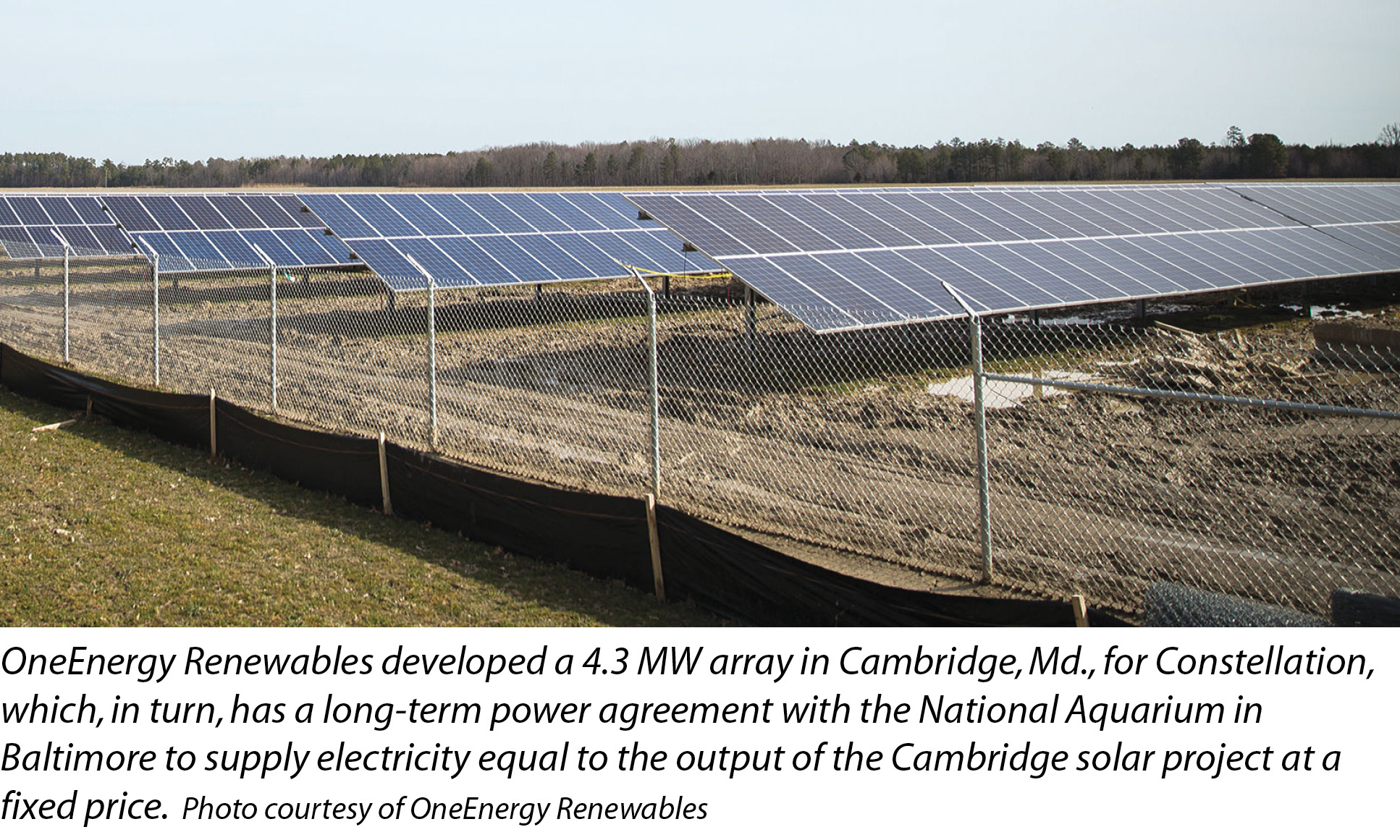

OneEnergy used this approach to develop a 4.3 MW array in Cambridge, Md., for Constellation, which, in turn, has a long-term power agreement with the National Aquarium in Baltimore to supply electricity equal to the output of the Cambridge solar project at a fixed price. Right now, the business is focused on one project for one customer, but OneEnergy envisions larger projects in the future with multiple off-takers.

“This really is just about selling the electrons,” Wright says. “I think there is going to be a trend toward more of a merchant approach in certain markets, where you are just aggregating the customer base for a large-scale solar project. Functionally, it looks more like community solar, but it is facilitated by the market, rather than by incentives and the regulatory environment.”

Distributed Generation Policies

How Market Deregulation Could Support DG Solar

By Michael Puttré

Some developers and energy providers are devising business models that transcend state policies.

si body si body i si body bi si body b

si depbio

- si bullets

si sh

si subhead

pullquote

si first graph

si sh no rule

si last graph